$3,000 a week? The enormous cost of care for elderly loved ones

[ad_1]

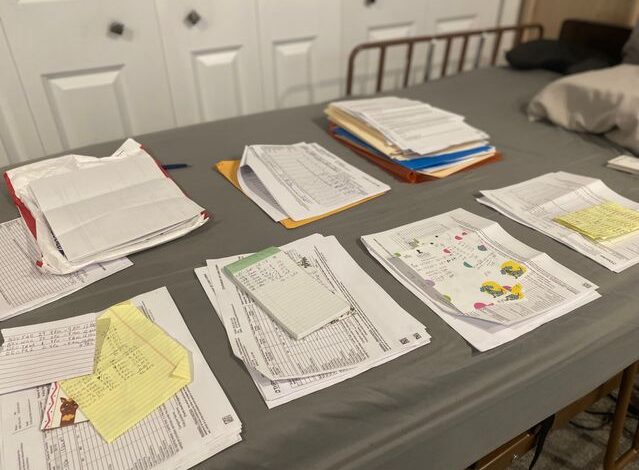

My mom is a model of financial organization and preparation, but since her health took a turn, I have found the one thing she can’t keep up on is the paperwork for her long-term-care insurance claim.

I came to help recently and had to delve into a stack of unopened premium bills with scary “last notice” stamps on them. There were also unfilled reimbursement forms going back four months and a trail of crumbs to find the information needed to complete them. I found little slips of paper stuffed in drawers with the caregiver hours scribbled on them. Thank goodness my mom uses a checkbook with carbon copies and still gets paper bank statements.

Beth Pinsker

My task is to assemble it all into bundles by caregiver (three regular ones and a floater), fill out one time sheet for each week with the hours, rate and tasks handled, and cut the check images so only the pertinent ones are with each bundle. Then I need to get everything signed by the caregivers and my mother.

Even with all this, I feel lucky. Once I sort it all out, the insurance company will process the claim and send reimbursement. Even the last premium will likely come back to her once the paperwork gets updated, because when you have an active claim, you get a waiver for the annual cost of the policy. That alleviates some of the sticker shock I felt when I wrote out the checks for a new week’s pay cycle for the caregivers. Ever since my mom started to need in-home care a year ago, I was aware it was expensive, but sometimes it takes dealing with the actual numbers to hit home the point.

There are lots of estimates out there for what caregiving costs American families on average, but it’s variable based on location and level of care. A nursing home typically runs $7,800 a month and assisted living is $4,500, according to Genworth. In-home care averages $27 an hour. But that doesn’t really give you much of a sense of what it will actually cost you when it’s your turn to decide what your loved one needs and what your family can afford.

Genworth has a cost-of-care calculator where you can assess the cost for your specifics, down to the hourly rate for in-home care in your city. That calculator says about $23 per hour where my mother is located, but that’s typically an agency rate. Private caregiving can be slightly less. If you average it out to $18 an hour, a week’s worth of full-time care comes to around $3,000 a week. That’s $12,000 a month, or $156,000 for a year.

That can be diced up a number of ways, but the reality looks something like three caregivers splitting shifts. One works weekdays 8 a.m. to 8 p.m., one works weekdays 8 p.m. to 8 a.m., and the third covers a 48-hour weekend shift. Every family does this a little differently. Some people only need daytime care, some only overnights, some don’t need weekends at all.

The Medicare myth

Many people think that Medicare covers these expenses, but that’s a misunderstanding. Medicare only covers limited stays in nursing facilities for acute needs. It doesn’t cover full-time care; just visiting nurse services like wound care. If you qualify for Medicaid because of low income and assets, that will cover in-home care or nursing home stays, but only at certain facilities and subject to availability.

Most of what you’re going to need for a loved one will come out of pocket, or you’re going to do it yourself. The reality is that caregiving is not possible at scale, and comes down to one-on-one attention.

Even with a loved one in an intensive care unit, where the nurse coverage is supposed to be two nurses to one patient, that doesn’t involve sitting with a scared person and just holding their hand. You’re going to want somebody in the room when the doctors come in at random times or somebody to go fetch ice or water instead of waiting. If your loved one needs memory care or has a physical limitation, they simply can’t be left alone.

“It’s all-consuming,” says Ann Brenoff, a retired columnist who spent two years caring for her ailing husband and recounted the tale in a book, “Caregivers are Mad as Hell! Rants from the Wife of the Very Sick Man in room 5029.” “It’s not for the faint of heart. I emerged from it a different person.”

Getting what you pay for

The private home-health aide network is unregulated, and agency policies vary. Assisted living facilities and nursing homes have different levels of regulation. Some are no more than glorified hotels and have about as much accountability, says Dave deBronkart, a longtime patient advocate who blogs as E-patient Dave. “Nobody can bust them for not doing what they say on their website,” he says.

DeBronkart and his sisters are currently battling over treatment their mother got last year in a private nursing home, where she never got the care she was promised and they had to move her out as fast as possible. His mother died this fall at 93—“she was like an alert captain watching her ship fall apart,” he says—and he’s furious that the U.S. doesn’t have a better system of patient care.

The medical system is set up to be cost-efficient, he says, “But nobody is accountable for whether the job gets done—and the job is patients’ needs getting taken care of. If it doesn’t happen, there’s no recourse.”

The best tip he has for patients is to make a friend on the inside and to look out for yourself and your loved ones. That means finding an advocate in your care network and keeping track of your own medical records. His sisters watched over every form of their mother’s like hawks, especially after the time one nursing home mistyped her medical record to transpose hyper- and hypothyroidism, which would have resulted in her getting exactly the opposite treatment she needed.

The cost of care and the precariousness of what you get for your money is what leaves many family members serving as caregivers. “The healthcare system has a big gap that causes family caregivers to exist—there’s nobody else who will do it,” says Brenoff.

The only real option for help to pay for outside caregivers is long-term-care insurance. It’s working for my mom for now, but it’s tricky to get a policy that’s worth an annual premium that could easily be $5,000 or more. Your best bet is if your workplace offers a group policy, which may lower the cost and the medical underwriting requirements that would eliminate you if you have major health conditions like diabetes or heart disease.

It’s also important to start as early as you can, because the premiums get increasingly expensive and the conditions to enter a claim can be restrictive. Once you do start to redeem benefits, the paperwork is onerous and you have to have cash on hand to lay out until the reimbursements come through.

As often happens with caregivers, my experience with caregiving has changed the way I think about my own future. I got my own long-term care policy through work a while back, and I think about maintaining my health as I go instead of waiting until it’s too late.

As Brenoff says, “The way I want to live is to be as healthy as I can for as long as I can. And I want to look forward and not back.”

Got a question about the mechanics of investing, how it fits into your overall financial plan and what strategies can help you make the most out of your money? You can write me at beth.pinsker@marketwatch.com.

More from MarketWatch

[ad_2]

Source link