AZ Alkmaar use BrainsFirst test to identify best young talent and it has helped them win UEFA Youth League | Football News

[ad_1]

In April, AZ Alkmaar won the UEFA Youth League by scoring 19 goals and conceding only twice in the knockout stages. Their triumph underlines their reputation as one of Europe’s best academies. It is a tale of talent identification and development.

But there is more to their success than scouting and coaching. The process of establishing which players they invest time in is a decade in the making. At AZ, they have been studying the brains of players as young as 12 to better understand their potential.

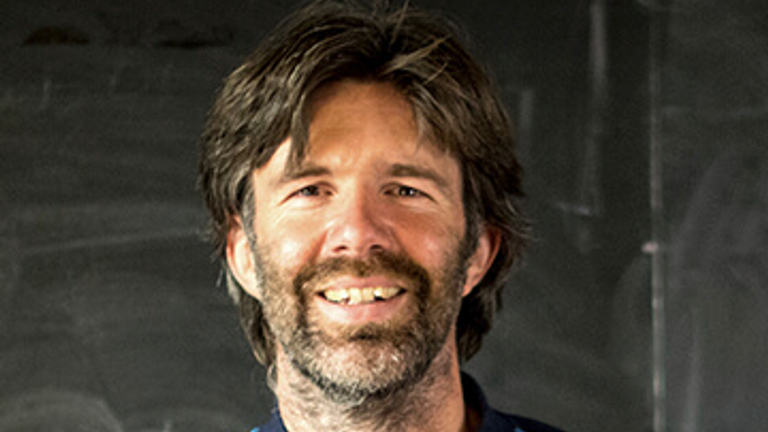

“AZ look for players who are not only outliers physically, mentally, tactically and technically but also cognitively,” Eric Castien tells Sky Sports. He is the founder of BrainsFirst, the organisation recruited by the Eredivisie club to test the brains of their youngsters.

“If you are at the elite level at 16, maybe even with the national team, but score poorly repeatedly on our tests, then AZ would most likely not hire you. It is about identifying future potential not primarily current performance as almost all clubs still do.”

It took four years for Castien and the neuroscientists at BrainsFirst to demonstrate that they could identify the brain functions required to be an elite player. Having done so, they needed six more to prove they could use it to predict future performance. Now they can.

Castien himself is no scientist, just an affable Dutchman with a curiosity that led him down this path. A former journalist, his journey began in 2011 when writing a book about talent identification at Real Madrid and Barcelona. Talking to the coaches was the spark.

“Everyone inside those academies knew all about talent and both clubs agreed that evaluating that talent came down to the four factors – physical, mental, tactical and technical. The problem was that there was a fifth element that they could not identify.

“Some of the coaches there called it magic. Others called it the black box. You either have it or you do not have it, but nobody knew what it was. Was it a third knee or an eleventh tooth? No, it was up here, inside the brain. That was the black box for them.

“They were not stupid. Intuitively, they understood that there was something decisive that they could not grab. They were aware of it, but could not decode it and transform it into tangible, actionable data. That is what we have done with clubs like AZ Alkmaar.”

The starting point was to speak to two neuroscientists at the University of Amsterdam. They scoffed at the notion of magic. The scientific explanation was clear. This was about brain function and not only was it not magic, but they were able to measure it.

Castien’s role was to marry the two worlds. Neuroscience, meet football. “I wanted to make a bridge between the two ways of thinking to decode the magic and understand game intelligence.” He visited the biggest clubs in the Netherlands to make his pitch.

“I explained to them that elite football was primarily not a physical activity but a brain activity. The muscles and the lungs are secondary. The brain is primary. You would call it magic. But you cannot measure magic and I can measure brain functions.”

By 2016, their tests, now conducted in the form of games, were able to challenge different parts of the brain, looking at memory, anticipation, attention span and self-control. “There are about 1,500 data points now so everyone does it differently,” says Castien.

As the bosses at AZ explained to him, that was when the hard work started. Football clubs are not purely academic facilities. They want to win and make money. It was one thing to identify what made an elite player. Their aim was to predict it.

Each AZ player had a test score, independent of the evaluations of the coaches. BrainsFirst told them which ones were in the green curve, those with greater cognitive potential. “We had to show that our group of approved players perform better over six years,” says Castien.

“That is what we did. One study showed that the group cognitively performing in the best 33 per cent within their age group developed a market value six to seven times higher than the lowest-performing group. It shows you need to be investing in the intelligent players.

“Everyone says that is logical. OK, are you telling me that you know that a 15-year-old player is intelligent enough to make it eight years later? You cannot. But we can. That is our function. We did not reinvent the brain. We just linked brain function to the pitch.”

When Castien begins to talk about measuring “the pre-frontal cortex at the front of the head” of a 12-year-old boy, it is easy to feel uncomfortable. This feels like something out of Minority Report, children found guilty of the pre-crime of not being smart enough.

Castien accepts the point. “I agree as a human being. It is harsh. But is not about general intelligence. We are not interested. It is about what makes you intelligent and whether this fits the context of elite football. To me, making talent decisions based on opinions and subjective reasoning is more unfair.” The tests are at least objective.

“After 16, if you are not in the green curve, you will not be in the green curve at 22. That is not a very attractive idea for people because they like to believe they can make anyone better. They can. But elite football clubs require players to be an outlier.

“It is why we never say categorically that this player will not make it. What we do say is that the probability is higher or lower. If you are having to compensate for a poor brain performance on football-specific skills then it is a low probability that you will make it at the elite level.

“At AZ, they use a threshold and the talents in the academy have to perform cognitively well enough. If they are not, and the other indicators are not super strong enough to compensate for it, they will say that it is unlikely the investment will bring a return.

“We are only giving the club this one piece of the puzzle. If this piece is not at a high level, then the investment is high risk. I know that sounds harsh but are you able to meet the requirements of the brain at Premier League level? Ninety-nine per cent cannot.”

Castien should know. He has done the tests himself on over one hundred occasions. He uses his own example to illustrate how difficult it is to be an elite athlete regardless of the body. He is a school-smart man. But he does not have the brain of an elite football player.

“My capacity for collecting information is high. I can process a lot of it. But it takes time. That is not good because on the pitch it needs to be fast. My reaction time is good. Good enough for elite football, even. But I cannot switch my attention fast enough.

“I am always two or three steps behind and it is not something I can train. It is how my brain works. It worked for me at school and at university. There, if you have a few minutes to collect information it is no problem. On the pitch, you do not have a few minutes.”

Castien wonders whether this might explain some of the differences even within elite football. “You will have seen it when a player moves from the Eredivisie to the Premier League, they say it is strange because the speed of their actions is too slow,” he adds.

“The reaction is to get the physical trainer to make them more explosive, try to make their legs stronger. Maybe that is a good idea. But it is also a good idea to find out whether the brain is sending the messages quickly enough to tell the muscles what to do.”

It is only likely to become more important. “Football today is becoming faster and more demanding. It is more complex. You do not have the classical winger any more. You have players swapping zones. That is more complex for the brain,” Castien explains.

“If you have less space and less time, you must solve the problems faster. It is not that we are saying that football requires smarter players, football is saying that football requires smarter players. We help them to identify those who can meet the requirements.”

In practice, it is highly likely that many of the best teams are already self-selecting. “Players such as Kevin De Bruyne and Ilkay Gundogan at Manchester City are good examples. I think Pep Guardiola intuitively understands that he needs those players,” says Castien.

“It is like at school. If you are teacher with 25 kids and five are highly gifted but you have to pay attention to those who are not, what happens is that the gifted kids become bored and frustrated. Maybe they start to underperform because they are not challenged.

“It is the same at football clubs. The trainer has to adapt the complexity and the speed of the training to the majority or even the cognitively weaker ones. That is not what you want because you want the training to be more demanding than the matches.

“As with the Navy Seals, the real-life situations should be less difficult than the situations you found yourselves put in during training. You need to train at a higher level than you need to perform but most of the time it is the other way around, unfortunately.”

All of which leads us back to AZ, where their commitment to identifying that ‘fifth element’ is giving them an edge on the rest. Others will catch up eventually. For now, they hope to enjoy first-mover advantage because of their appetite to think differently.

“There is a big difference between clubs. I do not think it will be news to anyone that the bigger clubs are accustomed to the thinking that if they make a mistake, they have enough money to correct the error. The challenger clubs need to be smarter than them.

“Clubs like AZ are much more open because if they are just going to copy the stronger teams they know they will lose. They have to do it differently so we help them to see talent differently and identify these blind spots when it comes to the talent pool.”

The might of Europe’s super clubs puts a check on AZ’s ambition. Money usually wins in the end. But scratch the surface and, on occasion, there will be a glimpse of where the best work is being done. In Geneva last month, football caught just such a glimpse.

AZ hammered Hajduk Split 5-0 in the final and it was no fluke. Prior to that they had already beaten Eintracht Frankfurt by the same score. In the last 16, Barcelona were beaten 3-0. In the quarter-final, it was Real Madrid on the receiving end of a 4-0 thrashing.

For Castien, the man who had been inspired by those Spanish giants to set about decoding the magic, it was a moment to reflect. “It was not just that they beat Barcelona and Real Madrid,” he says. “They did it with every one of those youngsters tested by BrainsFirst.”

[ad_2]

Source link